Down The Yosemite Creek

In general views the Yosemite Creek basin

seems to be paved with

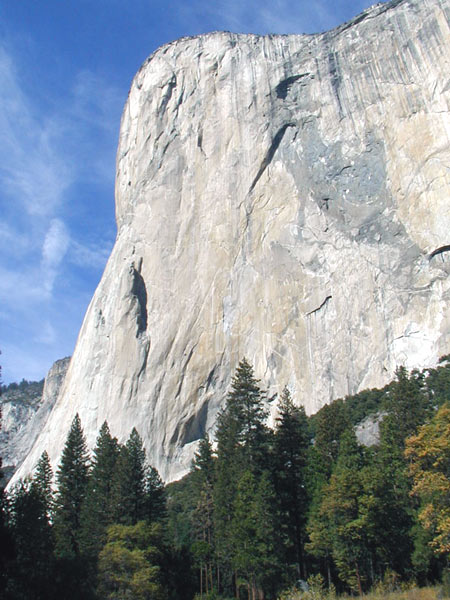

domes and smooth, whaleback masses of granite in every stage of

development--some showing only their crowns; others rising high and

free

above the girdling forests, singly or in groups. Others are developed

only on one side, forming bold outstanding bosses usually well fringed

with shrubs and trees, and presenting the polished surfaces given them

by the glacier that brought them into relief. On the upper portion of

the basin broad moraine beds have been deposited and on these fine,

thrifty forests are growing. Lakes and meadows and small spongy bogs

may be found hiding here and there in the woods or back in the fountain

recesses of Mount Hoffman, while a thousand gardens are planted along

the banks of the streams.

All the wide, fan-shaped upper portion of

the basin is covered with a

network of small rills that go cheerily on their way to their grand

fall

in the Valley, now flowing on smooth pavements in sheets thin as glass,

now diving under willows and laving their red roots, oozing through

green, plushy bogs, plashing over small falls and dancing down slanting

cascades, calming again, gliding through patches of smooth glacier

meadows with sod of alpine agrostis mixed with blue and white violets

and daisies, breaking, tossing among rough boulders and fallen trees,

resting in calm pools, flowing together until, all united, they go to

their fate with stately, tranquil gestures like a full-grown river. At

the crossing of the Mono Trail, about two miles above the head of the

Yosemite Fall, the stream is nearly forty feet wide, and when the snow

is melting rapidly in the spring it is about four feet deep, with a

current of two and a half miles an hour. This is about the volume of

water that forms the Fall in May and June when there had been much snow

the preceding winter; but it varies greatly from month to month. The

snow rapidly vanishes from the open portion of the basin, which faces

southward, and only a few of the tributaries reach back to perennial

snow and ice fountains in the shadowy amphitheaters on the precipitous

northern slopes of Mount Hoffman. The total descent made by the stream

from its highest sources to its confluence with the Merced in the

Valley

is about 6000 feet, while the distance is only about ten miles, an

average fall of 600 feet per mile. The last mile of its course lies

between the sides of sunken domes and swelling folds of the granite

that

are clustered and pressed together like a mass of bossy cumulus clouds.

Through this shining way Yosemite Creek goes to its fate, swaying and

swirling with easy, graceful gestures and singing the last of its

mountain songs before it reaches the dizzy edge of Yosemite to fall

2600

feet into another world, where climate, vegetation, inhabitants, all

are

different. Emerging from this last cañon the stream glides, in

flat

lace-like folds, down a smooth incline into a small pool where it seems

to rest and compose itself before taking the grand plunge. Then calmly,

as if leaving a lake, it slips over the polished lip of the pool down

another incline and out over the brow of the precipice in a magnificent

curve thick-sown with rainbow spray.

|