Chapter 3

Snow-Storms

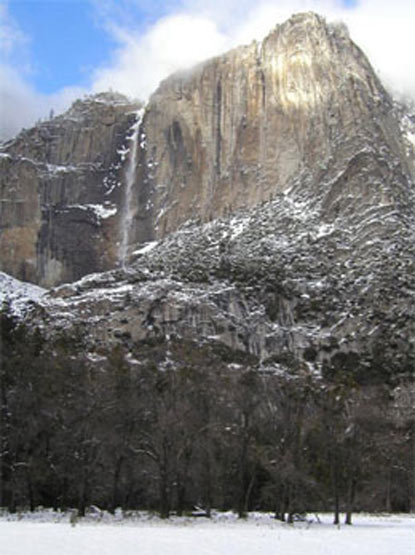

As has been already stated, the first of the great snow-storms that

replenish the Yosemite fountains seldom sets in before the end of

November. Then, warned by the sky, wide-awake mountaineers, together

with the deer and most of the birds, make haste to the lowlands or

foothills; and burrowing marmots, mountain beavers, wood-rats, and

other

small mountain people, go into winter quarters, some of them not again

to see the light of day until the general awakening and resurrection of

the spring in June or July. The fertile clouds, drooping and condensing

in brooding silence, seem to be thoughtfully examining the forests and

streams with reference to the work that lies before them. At length,

all

their plans perfected, tufted flakes and single starry crystals come in

sight, solemnly swirling and glinting to their blessed appointed

places;

and soon the busy throng fills the sky and makes darkness like night.

The first heavy fall is usually from about two to four feet in depth

then with intervals of days or weeks of bright weather storm succeeds

storm, heaping snow on snow, until thirty to fifty feet has fallen. But

on account of its settling and compacting, and waste from melting and

evaporation, the average depth actually found at any time seldom

exceeds

ten feet in the forest regions, or fifteen feet along the slopes of the

summit peaks. After snow-storms come avalanches, varying greatly in

form, size, behavior and in the songs they sing; some on the smooth

slopes of the mountains are short and broad; others long and river-like

in the side cañons of yosemites and in the main cañons,

flowing in

regular channels and booming like waterfalls, while countless smaller

ones fall everywhere from laden trees and rocks and lofty cañon

walls.

Most delightful it is to stand in the middle of Yosemite on still clear

mornings after snow-storms and watch the throng of avalanches as they

come down, rejoicing, to their places, whispering, thrilling like

birds,

or booming and roaring like thunder. The noble yellow pines stand

hushed

and motionless as if under a spell until the morning sunshine begins to

sift through their laden spires; then the dense masses on the ends of

the leafy branches begin to shift and fall, those from the upper

branches striking the lower ones in succession, enveloping each tree in

a hollow conical avalanche of fairy fineness; while the relieved

branches spring up and wave with startling effect in the general

stillness, as if each tree was moving of its own volition. Hundreds of

broad cloud-shaped masses may also be seen, leaping over the brows of

the cliffs from great heights, descending at first with regular

avalanche speed until, worn into dust by friction, they float in front

of the precipices like irised clouds. Those which descend from the brow

of El Capitan are particularly fine; but most of the great Yosemite

avalanches flow in regular channels like cascades and waterfalls. When

the snow first gives way on the upper slopes of their basins, a dull

rushing, rumbling sound is heard which rapidly increases and seems to

draw nearer with appalling intensity of tone. Presently the white flood

comes bounding into sight over bosses and sheer places, leaping from

bench to bench, spreading and narrowing and throwing off clouds of

whirling dust like the spray of foaming cataracts. Compared with

waterfalls and cascades, avalanches are short-lived, few of them

lasting

more than a minute or two, and the sharp, clashing sounds so common in

falling water are mostly wanting; but in their low massy thundertones

and purple-tinged whiteness, and in their dress, gait, gestures and

general behavior, they are much alike.

|